The Hovertrain Concept

Think about what a train wheel looks like – it’s not a simple round wheel like you would see on a car. There is a flange, the part of the wheel that fits inside the rail, keeping the train on the tracks. If you drive a normal train faster than about 140 mph, you get a phenomenon called hunting oscillation. This is where the flanges start to hit the inside of the rail more and more often the faster you go, producing a “shuddering” effect. Not only does this effect slow the train down, but if you push the train to go even faster, the results can be disastrous.

The British were the first to develop the marine Air-Cushioned Vehicle (ACV), and its land-based counterpart, the Ground Effect Machine. The generic term for this type of vehicle is a “hovercraft”, because it hovers above the ground on a cushion of air. In 1967, British engineers at Tracked Hovercraft Ltd. were developing Tracked Hovercraft as a potential solution to the hunting problem (because there are no train tracks or flanged wheels). The vehicle would be moved using a Linear Induction Motor, which was being developed at the same time at Imperial College London. Testing had begun using an unmanned prototype and an elevated guideway, but a change in British government in 1973 halted funding for the project.

The Pueblo Test Center Takes Notice

By the late 1960s, the Office of High Speed Ground Transportation (OHGST) – the operator of the Pueblo Test Center – was closely monitoring the British efforts. In 1969, an engineering study by technology company TRW recommended a U-shaped guideway for the vehicle. OHGST concluded that a Hovertrain might be practical, and the only way to find out if it could really work was to test a full-size prototype. NASA and several private contractors began researching vehicle designs. NASA’s involvement is the reason why the front of the Grumman looks so much like the Space Shuttle. Meanwhile, MIT and Princeton worked on ways to use incoming air to create the air cushion which would raise the vehicle.

Enter The Grumman

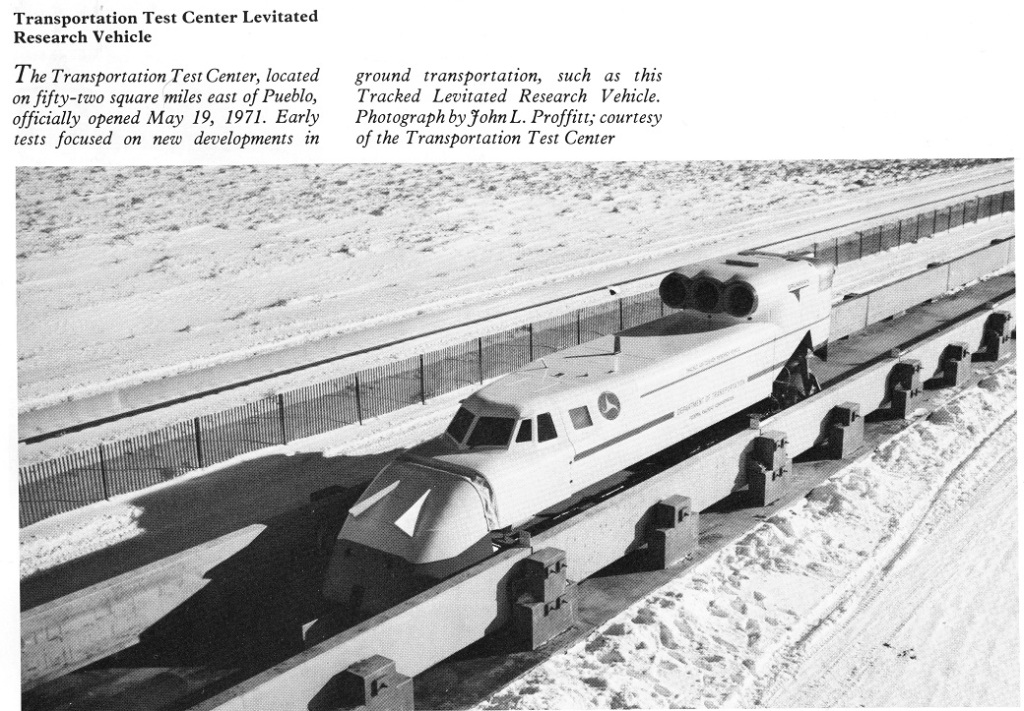

In March 1970, Grumman Aerospace Corporation started design of their Tracked Levitated Research Vehicle (TLRV). This vehicle was a true hovertrain, intended to run inside of a concrete U-shaped track on a cushion of compressed air, with no wheels. The Grumman gets its levitation power from the three huge turbofan engines on the top of the vehicle. The TLRV was a test bed for evaluating the performance of air levitation cushions and suspension systems. Although the concept was designed to reach speeds of up to 300 mph, the prototype vehicle never approached those speeds. In April 1972, just two years after starting the design, the prototype hovertrain was ready for its first public display. In early June, “The Grumman” was shown at the U.S. International Transportation Exposition, aka “Transpo ’72”. Later that month, the vehicle arrived at the High Speed Ground Test Center in Pueblo.

The Grumman Under-achieves

The original test plan called for a 22-mile oval U-shaped guideway, 8 miles long and 5 miles wide – as big as the Test Center property could accommodate. But construction of the guideway was delayed six months because other construction projects were given higher priority. Nearly a year passed before the first 1.5 miles of guideway was completed in March 1973, with another 1.5 miles completed in November. Initial testing was fraught with design glitches – issues with motor controls, power equipment and water cooling. Even the ability to accurately measure the air gap underneath the vehicle was a challenge. At first, the Grumman used “aero-propulsion” to move forward, using exhaust from the same three turbofan engines that gave the vehicle its lift. The fastest speed achieved by the Test Center using this method of propulsion was 91 mph in 1973 – far short of the 300 mph vision.

Leveling Up The Grumman – Almost

Electric propulsion equipment replaced the Grumman’s aero-propulsion system in December 1973 to increase its potential speed and help compensate for the short track. The intent all along was to add a reaction rail on the bottom of the guideway to test the LIM propulsion. The Test Center had the LIM motor installed in the vehicle, all tested and ready to go. Engineers were eager to test their predicted speeds of 240 mph for the Grumman hovertrain. But by this time, there was no money left in the budget to manufacture and install new reaction rail. Using reaction rail surplus “leftovers” from other projects, including the Garrett LIMRV (one of our other Rocket Cars), engineers at the Test Center were able to piece together only 1500 feet of reaction rail for the Grumman’s three-mile track. This 1500 feet includes not just the 23-inch reaction rail, but also an 8000-volt electrical “wayside” power supply, similar to the one used by the Rohr Aerotrain. The Grumman was in the midst of low speed tests on this new track, when funding from the Department of Transportation ran out in August 1975. The test program for the Grumman ended the following year.

Slideshow: The Grumman at the Pueblo High Speed Test Center

Slideshow: The Grumman at the Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum

Slideshow: The Grumman is moved to the Pueblo Railway Museum, April 2010

Copyright © 2023, Pueblo Railway Foundation