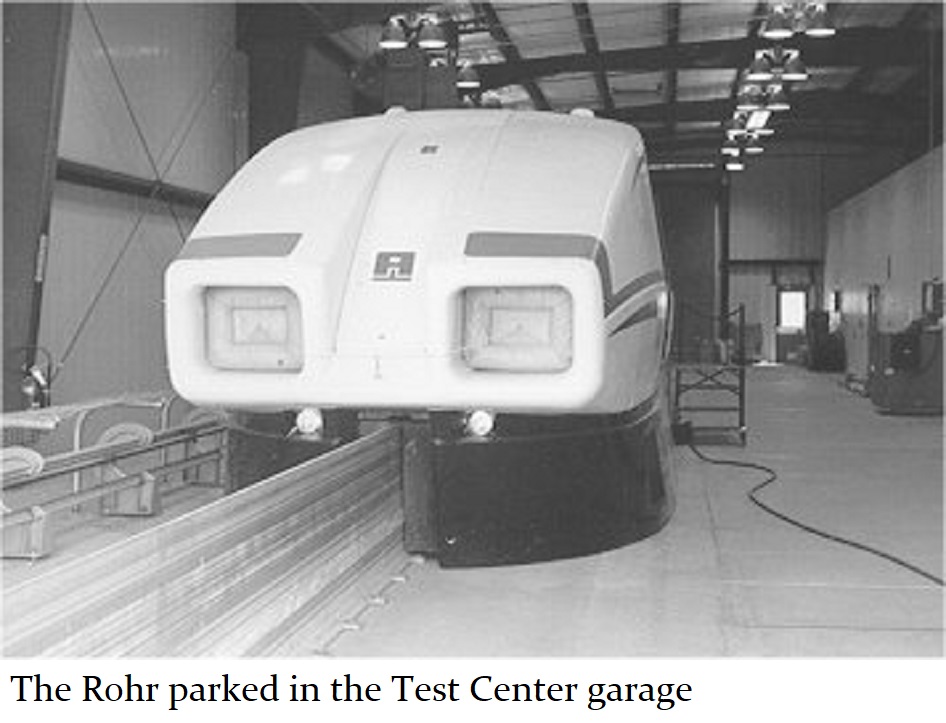

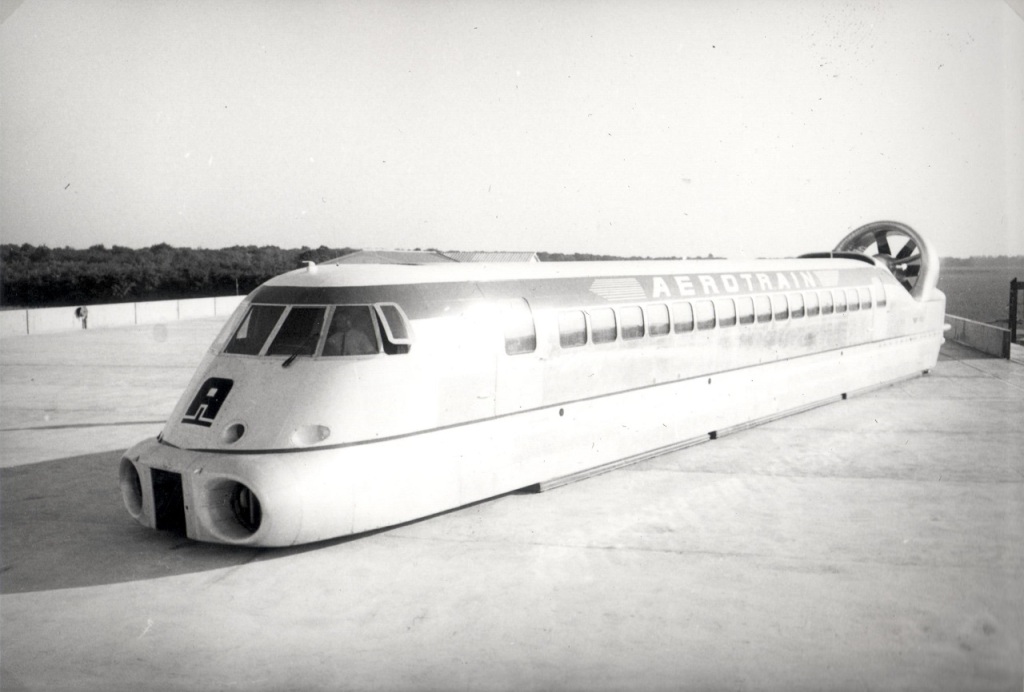

The Aerotrain was an experimental Tracked Air Cushion Vehicle (TACV), developed in France starting in 1965 under the engineering leadership of French scientist and inventor Jean Bertin. The Rohr vehicle straddles a 33-inch high aluminum “inverted-T” reaction rail, with no other rails or wheels on the ground. In operation, the vehicle is supported on a thin cushion of air, and propelled forward by its Linear Induction Motor. The interior of the Rohr looked like the first class cabin of a jet airliner, and was designed to seat 60 passengers.

The Last Of Its Kind

Five Aerotrain prototypes were built. Only three of these were full size. Two small-scale prototypes are preserved in France. The group preserving these Aerotrains is the “Association of the Friends of Jean Bertin”, a group of Aerotrain engineers and enthusiasts. Two full size prototypes, the “S-44” and the “I-80”, were also built in France. But two separate fires destroyed those two prototypes in 1991 and 1992. The fire that destroyed the I-80 on March 22, 1992 was arson, just a few days before the vehicle was to be moved to a museum.

The Rohr is the only full-size prototype Aerotrain left.

The Rohr’s Early Years

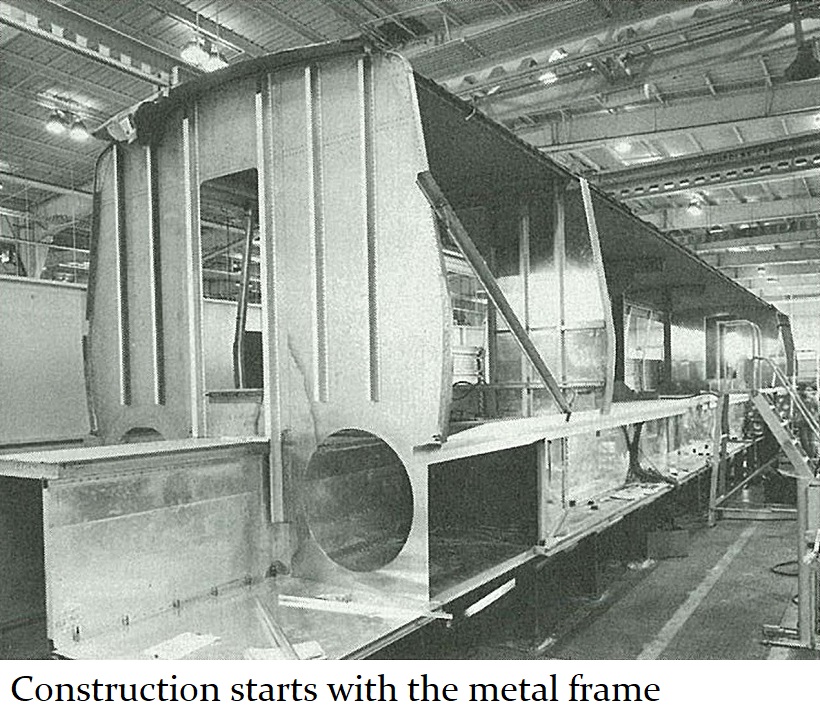

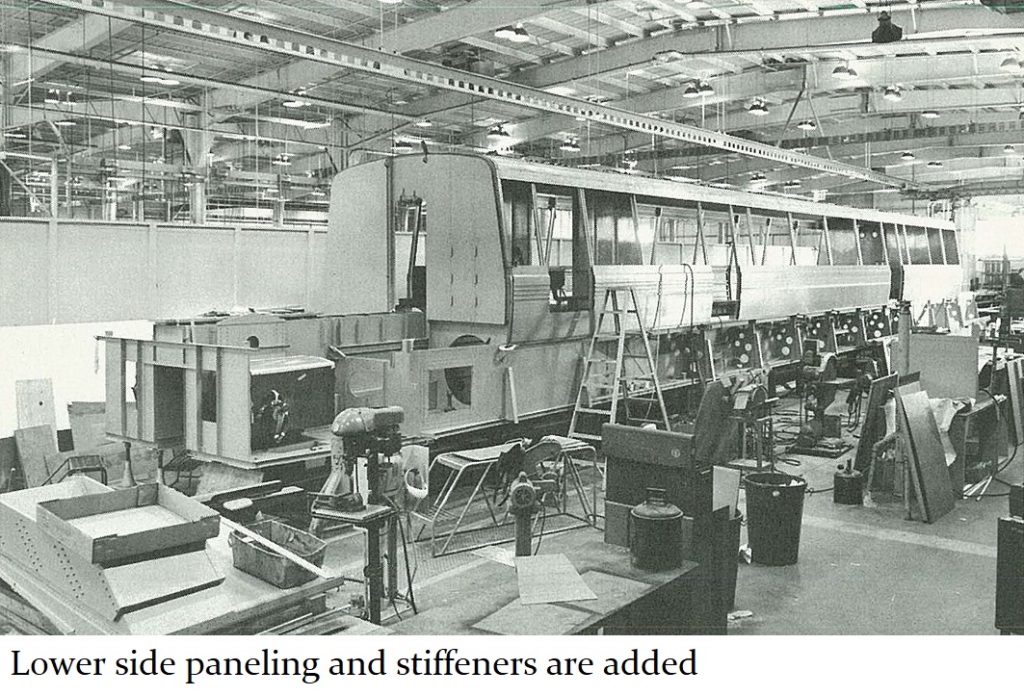

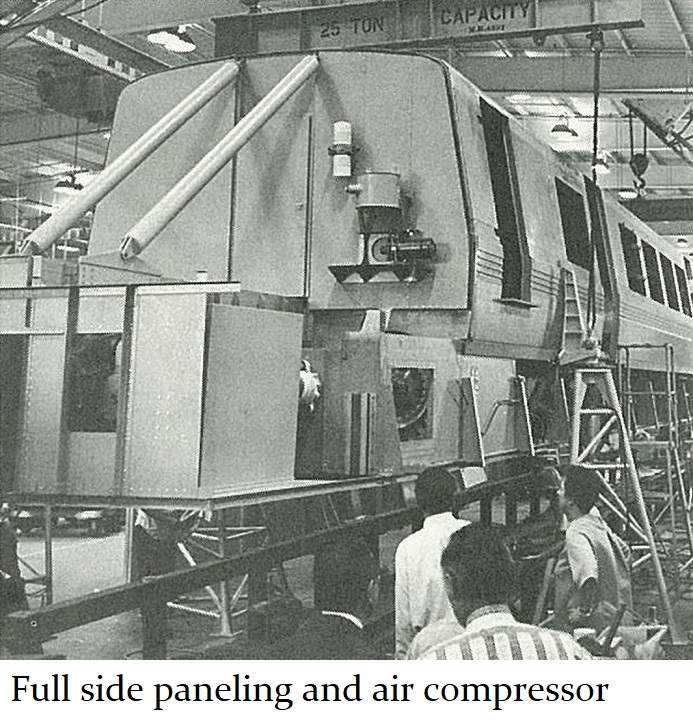

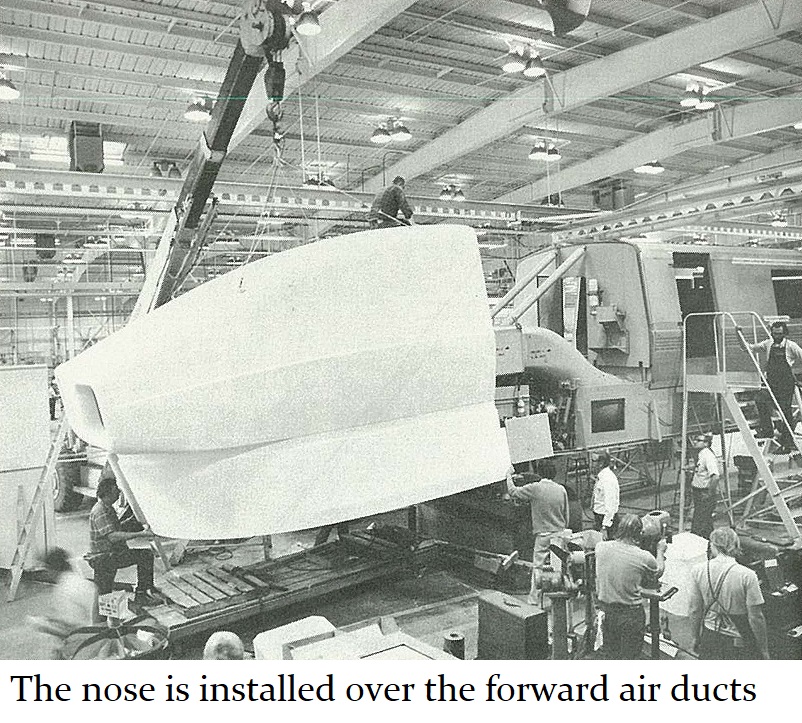

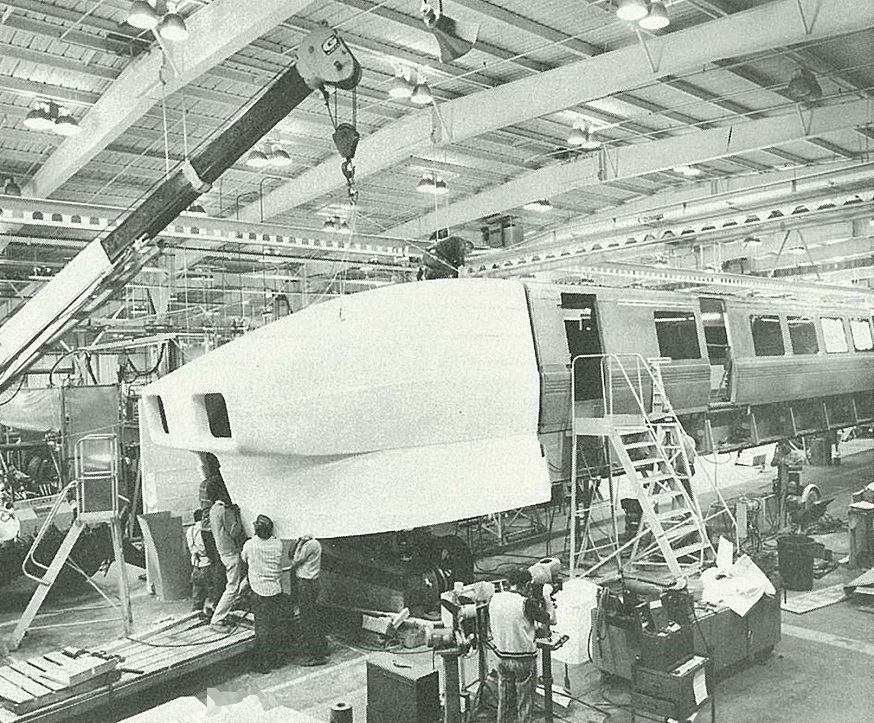

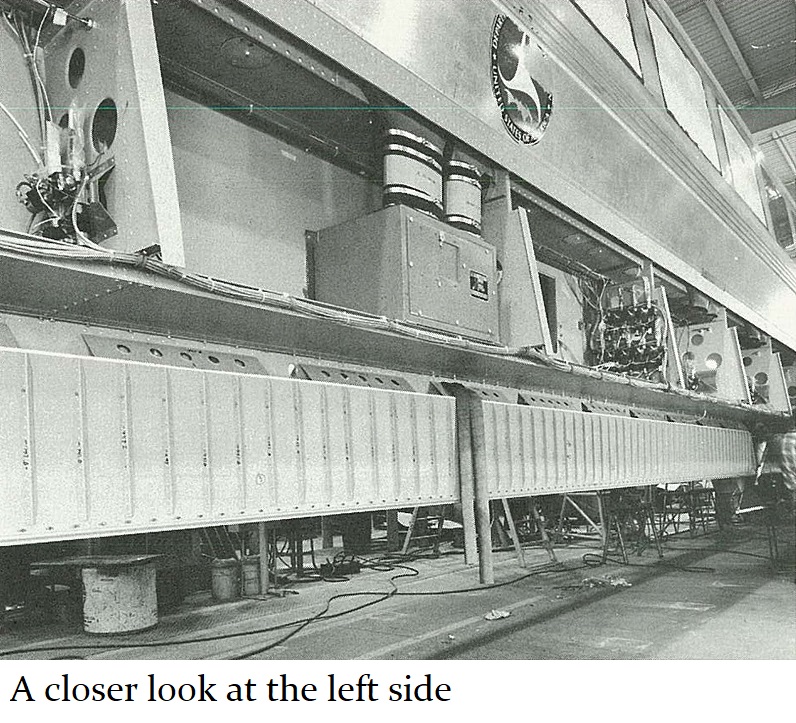

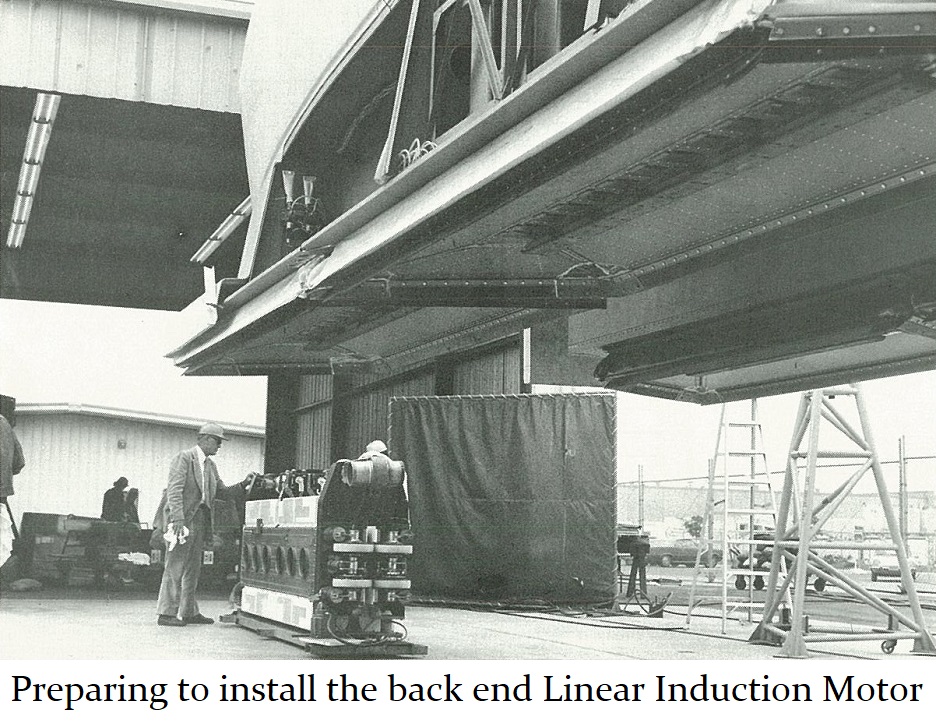

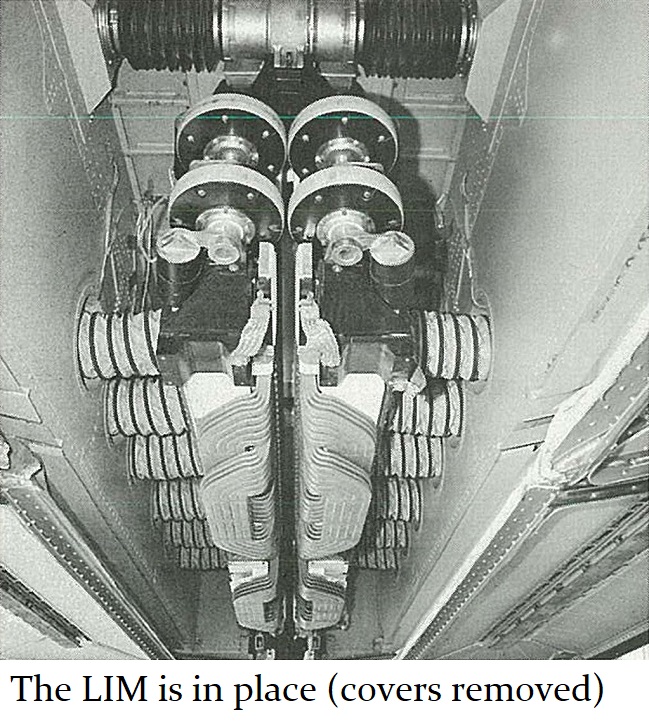

In 1969, U.S. company Rohr Industries, Inc. licensed technology from French company Aerotrain to build their designs in the U.S. In 1970, the U.S. Secretary of Transportation directed development of a prototype electric-driven Tracked Air Cushioned Vehicle (TACV) for airport access (city center to airport) applications. Around the same time, construction of the Rohr Aerotrain had begun at the Rohr Industries plant in Chula Vista, California. Rohr built a short 500-foot track at their Chula Vista plant for limited low speed tests. In mid-1971, the DOT awarded a contract to Rohr Industries to build and test their Aerotrain at the newly opened High Speed Ground Test Center in Pueblo.

Slideshow: Aerotrain construction at the Rohr Industries plant in Chula Vista, California

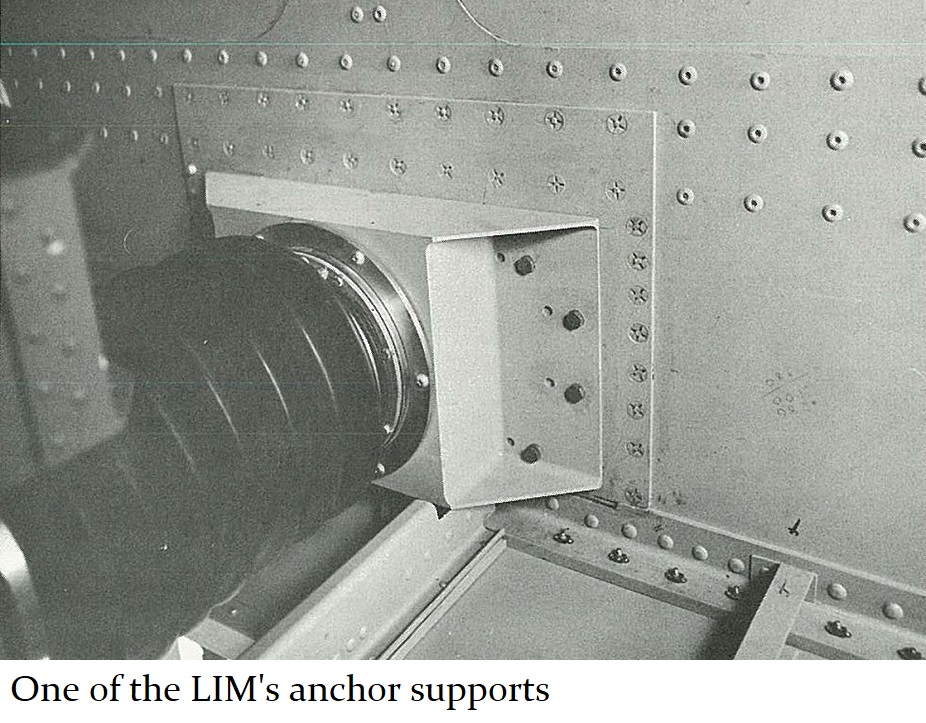

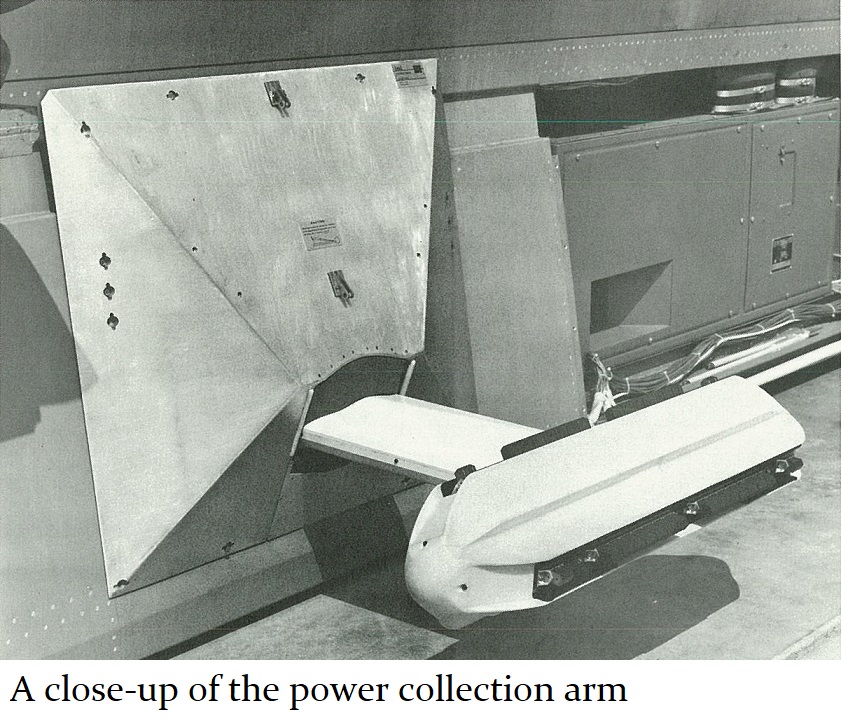

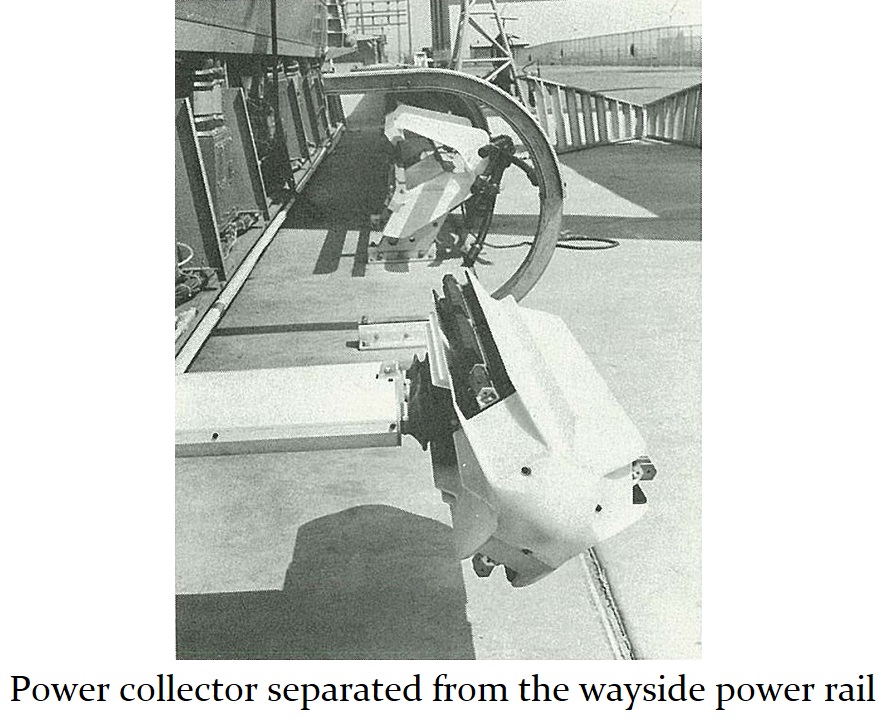

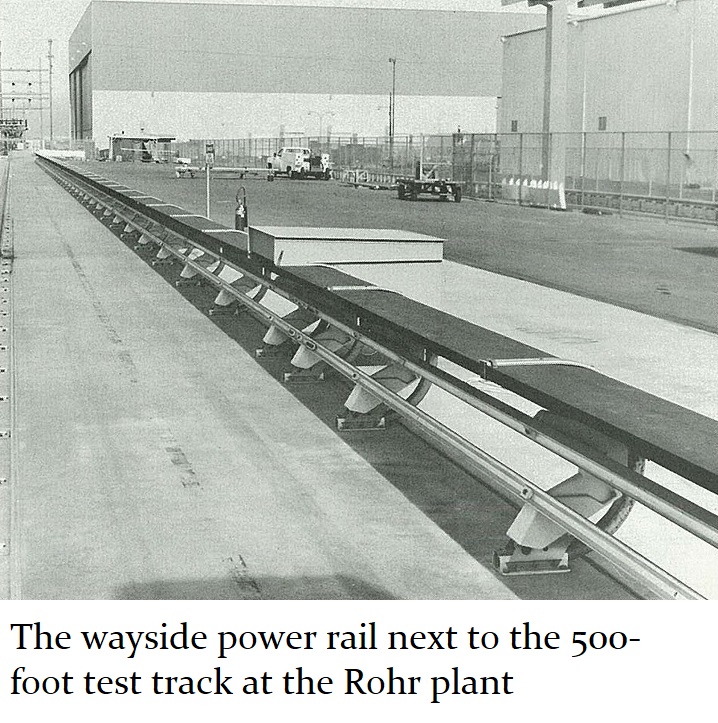

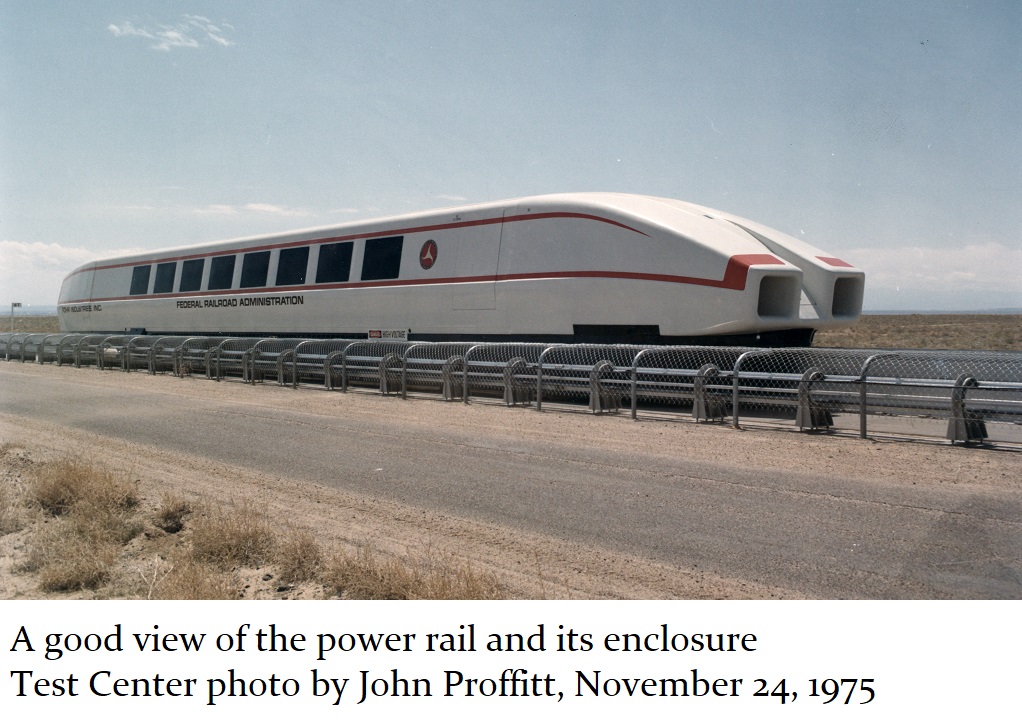

A “Concern” About The Design

Off to one side of the vehicle, there was a three bar side-rail, called a wayside by the engineers, which supplied electrical power to the vehicle as it moved. In May of 1971, the Pueblo Test Center that would be testing the vehicle called out the side-rail electrical system as a source of “concern”. In commercial practice, the notion of having to build an electrical side-rail along the entire length of the Aerotrain’s track looked like an expensive proposition. The Test Center began researching “on-board” electrical power alternatives in the form of advanced external combustion engine designs. It’s worth noting here that at the same time the Rohr was being developed in the U.S., similar Aerotrains were being tested in France without the side-rail in their design.

It would be another three years before the Rohr Aerotrain was ready for testing at the Test Center.

Slideshow: The Rohr’s power collection arm

Late To The High Speed Party

By May of 1973, testing was already underway at the Pueblo Test Center for both of our other two “Rocket Car” prototypes, the Grumman and the Garrett. The Garrett had already been under test at the Test Center for two years. But it was only then, in May of 1973, that construction began on the inverted-T guideway for the Rohr. Meanwhile, the Rohr engineers in Chula Vista had identified another potential issue – noise. Testing results showed that the Rohr failed to meet noise criteria, both inside and outside, under “hovering” conditions.

The Engineers Push The Envelope

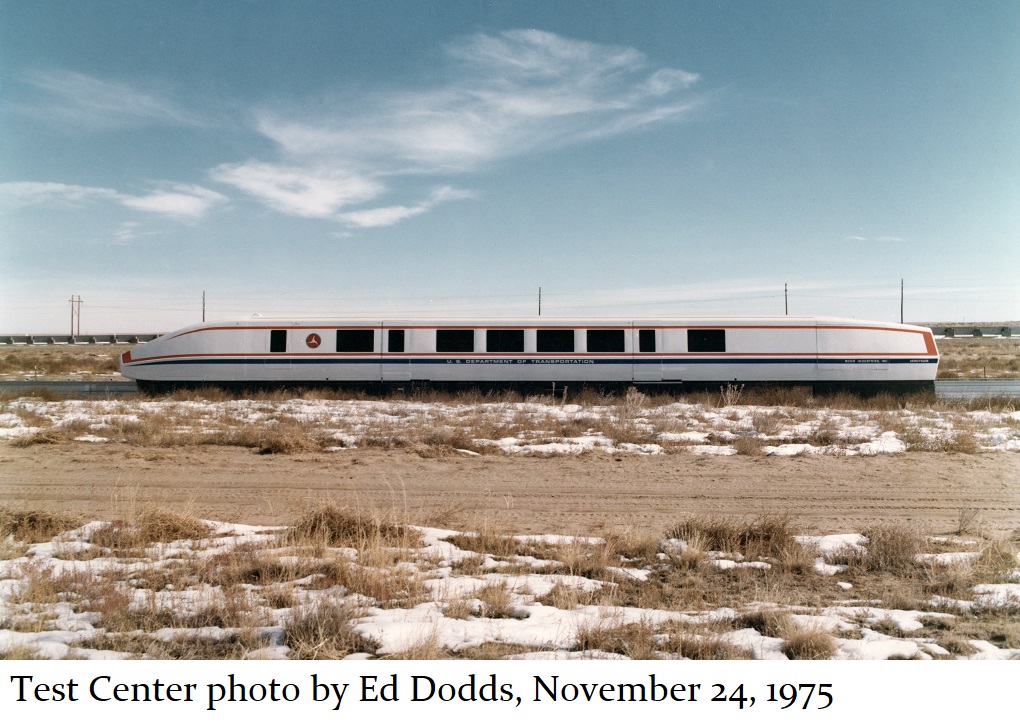

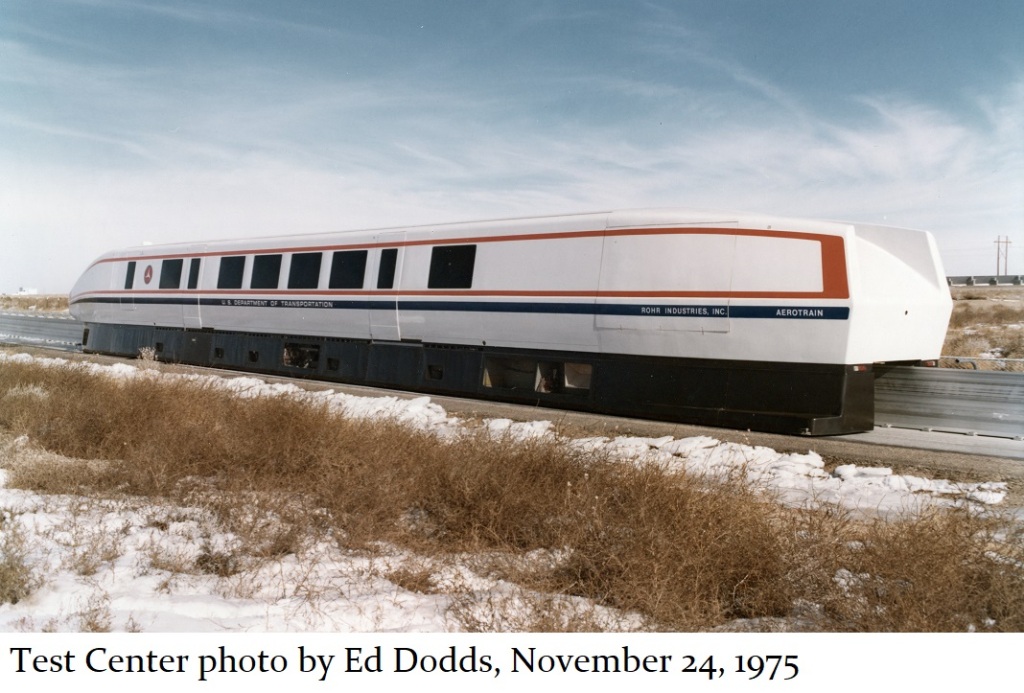

Testing of the Rohr at the Test Center began in September 1974, funded in part by a one year Phase 3 Department of Transportation contract for $550,000. After several months of low speed tests on its limited 3.13 mile track, the Rohr’s test track was eventually extended to 5.68 miles. On May 9, 1975, the Rohr reached a speed of 102 mph, a U.S. record at the time for levitated vehicles. The following year, the testing team smashed that record on their new longer track, taking the Rohr to 145 mph. The TTC engineers also managed to solve the noise problem, quieting the Rohr down to a level comparable to other forms of passenger ground transportation.

Slideshow: Photos of the Rohr Aerotrain near the end of its testing at the TTC

Insurmountable Odds

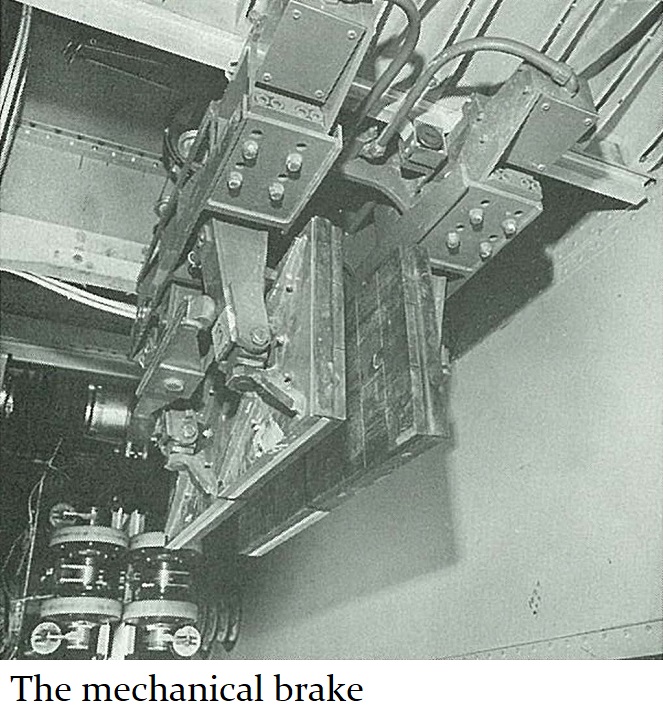

The late start of testing for the Rohr was just the first of a series of events that would conspire to end development of the Aerotrain. On May 19, 1974, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was elected President of France, following the death of Georges Pompidou. d’Estaing’s commitment to improving the existing rail systems prompted him to terminate the contract, signed just one month earlier, for an Aerotrain line that was to have been built in northwest Paris. While the French Government was turning its back on the Aerotrain, in Pueblo, the Rohr was a victim of bad timing. The other two Rocket Cars, the Grumman and the Garrett, had arrived at the Test Center first, and had already consumed nearly all of the available funding allocation from the DOT, leaving very little money for the Rohr. In testing, the Aerotrain was performing to specifications, but it was deemed unfeasible due to excessive power requirements. The wayside electrical infrastructure had to supply over 2 megawatts of power, at over 4000 volts, to the vehicle. Despite the short track length, it took two electrical substations, one on each end, to generate enough power. Then in June 1975, another setback – while in its garage, a procedural error in starting up the Rohr overheated a section of the reaction rail. The resulting heat damage to the Linear Induction Motor delayed testing for three months. During this delay, project funding from the DOT to the High Speed Test Center ran out, in August of 1975. With no additional funds forthcoming, the Rohr prototype Aerotrain was mothballed two months later. Finally, on December 21, 1975, the death from cancer of the Aerotrain’s inventor and driving force, Jean Bertin, dashed any hopes of the Aerotrain’s revival.

Before the Rohr Aerotrain testing project was completely closed down, TTC gave one day of demonstration rides in June 1976.

The Rohr Is Donated

The Rohr needed a new home, so the TTC donated it to the City of Pueblo, Colorado, on the condition that it be displayed in a museum setting. Around 1977, the Rohr Aerotrain was moved from the TTC to the Pueblo Aircraft Museum, where it remained outdoors, exposed to the elements for 30 years.

Slideshow: Photos of the Rohr Aerotrain at the Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum

The Aircraft Museum Expands

In 2008, the Pueblo Aircraft Museum was preparing to build an additional hanger for preserving numerous historical aircraft that were suffering in the high-country weather of Pueblo, Colorado. While the Grumman and Garrett vehicles were not at risk immediately from these expansion plans, the Rohr’s location was directly in the path of the new hanger. Both the City of Pueblo and the Aircraft Museum approached the Pueblo Railway Museum to quickly accept possession of the Rohr or it would be scrapped.

The Rohr Is Donated … Again

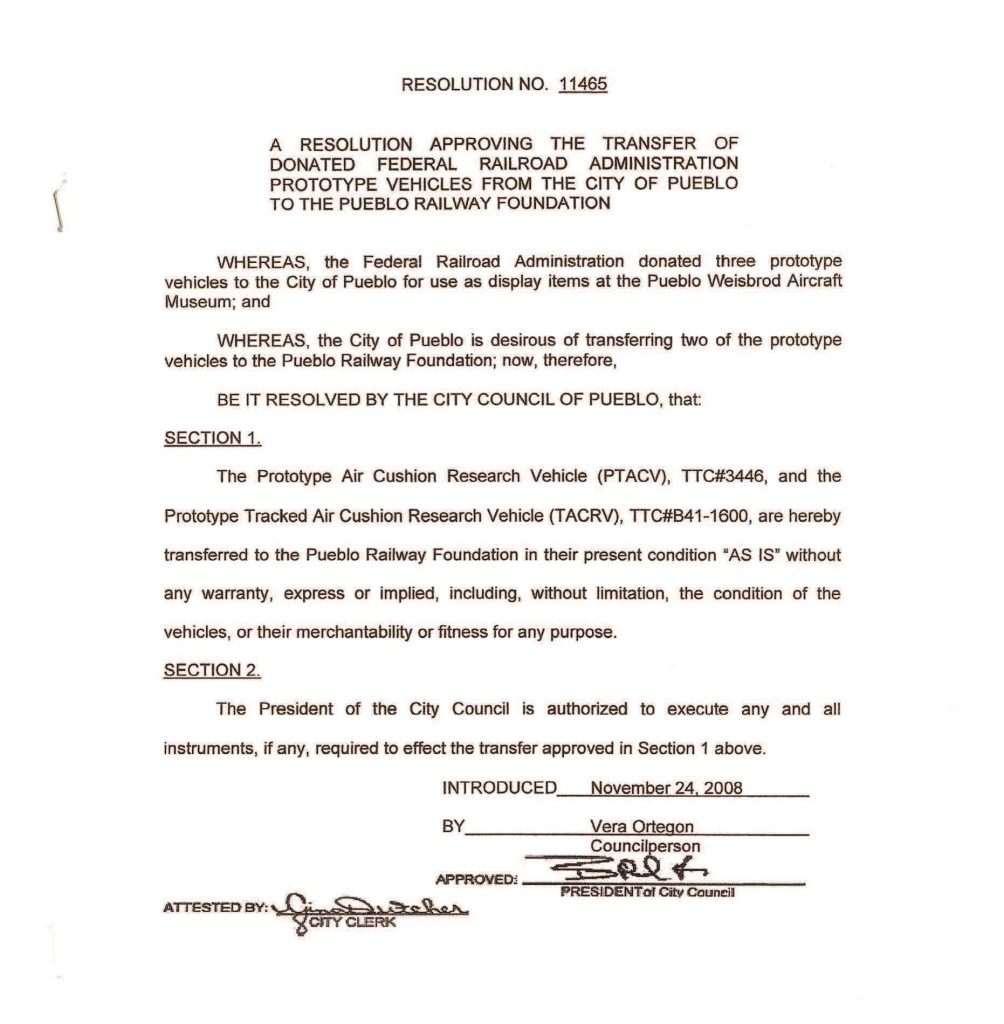

The idea of the PRM acquiring the three Rocket Cars had been in discussion for some time, but at first, the PRM didn’t have a location for the vehicles. That changed when members of Rio Grand Yard LLC acquired property near the PRM’s collection, and gave the Railway Museum permission to use the property. While a new location for the vehicles was being finalized, the Railway Museum and the Aircraft Museum worked to legally transfer ownership of the vehicles. The City demonstrated its ownership of the Rohr, and the two museums established their intent to transfer ownership. On November 24, 2008, Pueblo City Council made an official declaration transferring ownership of the Rohr to the Pueblo Railway Foundation. But the actual physical move of the Rohr from the airport to the PRM would be costly. The Aircraft and Railway Museum are both 501(c)3 non-profit organizations, and these types of charities don’t generally have a lot of spare cash. Neither organization had the funds to pay for the transport of any of the three rocket cars. Funds to move the Rohr were provided as a loan from several Railway Museum members.

A Technical Challenge

Perhaps the most interesting problem to be solved regarding the physical move was figuring out how to lift the Rohr without damaging it. Luck was with the PRF though, as many engineering drawings had been stored inside the vehicle. A drawing was found which described four lifting brackets that had been used twice before – when the Rohr arrived at the Test Center, and later when it was moved to the Aircraft Museum. After an extensive search however, the original brackets couldn’t be found, so they were fabricated by Railway Museum members who donated their time and talent to this critical task. These brackets took six months to design and fabricate, but without them, moving the Rohr to the PRM would be impossible.

Slideshow: James, Michael and Vincent Dandurand attach the mounting brackets to the Rohr, March 16, 2009

On July 14, 2009, the Rohr Aerotrain was moved eight miles from the Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum to its new home at the Pueblo Railway Museum.

Copyright © 2023, Pueblo Railway Foundation